Water scarcity has contributed to an “arc of instability” characterized by conflict and displacement that stretches from West Africa to the Middle East, said a panel of experts at the Wilson Center on March 1. Two authors from an upcoming compilation of case studies on water security and violent conflict by World Wildlife Fund gave overviews of challenges in Nigeria and Iran and recommendations for U.S. engagement.

The lack of good governance is a “striking commonality” across the arc, said Julia McQuaid, senior researcher and project director at the CNA Corporation. The failure of governments to address growing water scarcity, relieve drought conditions, and defuse communal tensions has contributed to a rise in insurgent groups and migration.

Nigeria, Bone Dry and on Fire

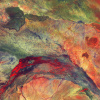

In northern Nigeria, 2.6 million people have been displaced since last summer due to a famine “that’s only becoming fully realized now and receiving national attention,” said Marcus King, John O. Rankin associate professor and director of International Affairs Program at George Washington University.

Not only have hundreds of villages been abandoned to escape drought, but many of the same people are on the run from Boko Haram, the Islamic terrorist group that has waged an insurgency against the Nigeria state since 2010. “Lack of water in the areas where people have been pushed into has really weakened the resilience of these populations to further attacks by Boko Haram,” said King.

Meanwhile, in the south of the country, conflict has re-emerged in the Niger Delta. The primary ecological concern for the region is man-made, said King. Spills from oil and natural gas extraction and violent opposition by rebels have degraded the water, agricultural land, and fisheries. The Niger Delta Vigilante group has attacked oil company infrastructure and personnel, calling for better provision of clean water and equitable rights, King said, but “ironically these attacks also frequently cause severe pollution of the same water resources that they were seeking to protect to begin with.”

These conflicts matter to the United States because Nigeria is a “linchpin of regional stability and a strategic partner in the fight against extremism,” said King. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country and a major contributor to international peacekeeping operations. The instability in the north of the country in particular is having ripple effects beyond its borders and into Europe, contributing to a “migratory arc of instability stretching from West Africa through the Maghreb and eventually across the Mediterranean Sea,” said King.

Tensions in Iran

Iran has received less attention for its water problems, but they’re no less severe, said David Michel, a non-resident fellow at the Stimson Center. About 90 percent of Iran’s land is arid or semi-arid, and monthly water withdrawals for more than half of the country exceed available resources by three to five times, he said. “Freshwater withdrawals now top 67 percent of annual renewable resources, whereas 40 percent withdrawal to availability ratio is considered a threshold of water stress.”

“Mismanagement aggravates [and] magnifies Iran’s water challenges,” Michel said. Agricultural policies subsidize certain staple crops, consequently encouraging excess irrigation. The government has also built a system of dams and canals to transfer water across the country, creating internal tensions over “winners and losers” while doing little to address scarcity, as demand simply rises to meet the new supply.

“Competition over scarce water resources has already sparked local conflicts within the country and is increasingly generating clashes between Iran and its neighbors,” Michel said.

Iran shares water resources with Iraq in the west, as the upstream country, and Afghanistan in the east, as the downstream country. In 2011, Iranian troops actually crossed into Afghanistan to release water from a canal to ensure it wasn’t diverted before reaching the border, Michel said. Iran considers increases in water infrastructure spending and demand in Afghanistan a threat to its tenuous water security and is responding on multiple fronts. At times the government seems to support water development in its neighbor, contributing funds to infrastructure projects, providing technical aid to the water ministry, and engaging in diplomacy, Michel said. But Afghanistan has also accused Iran of supporting Taliban attacks on infrastructure projects.

Michel said it is unlikely that the Iranian government will ever be overthrown because of dissent over water issues, but you can see pressure exerting an influence on domestic politics, for example in the creation of a National Water Conservation Plan by President Rohani.

Implications for U.S. Engagement

The conflicts dotting the arc of instability, including also in Syria and Iraq, are emblematic of how the environment is thought to interact with violent conflict generally. They are mostly sub-national conflicts, between non-state actors, with multiple causal factors, McQuaid said, including “economic, political, social, and – increasingly – ecological grievances.”

There is little evidence that water stress itself is a direct cause of conflict, said McQuaid, who is leading a research project at CNA on whether global water stress matters to U.S. national security. “What water stress conditions can do, and tend to do, is to act as an additional stressor or multiplier on top of preexisting challenges.”

Military leaders that McQuaid works with at CNA sometimes question whether water is important at all then, if just one of many stressors. “The answer is a resounding, yes,” McQuaid says. “Our research shows that it is a factor, and that as water stress gets worse, as it’s projected to do, it will likely play an increasing role as a factor in instability and conflict.”

Syria and Iraq’s greatest drought on instrumental record, from 2007 to 2010, created conditions of food insecurity, mass migration, and widespread discontent over the government’s ineffective response, said King. “The areas in Syria that were most affected by these conditions were where ISIS made their first territorial gains.”

McQuaid recommended building relationships with foreign partners and military leaders to further develop and discuss the notion that water can contribute to instability. “Understanding and factoring in the root causes and underlying drivers of conflict and instability in this part of the world can lead to more effective approaches to dealing with them both for the U.S. and for our partners,” she said.

The failure of governments to respond is sometimes down to a lack of awareness or because “they simply don’t have the tools, the technology, the know-how to respond in a way that can help,” said McQuaid. As the United States’ assets for providing technical expertise, data, and early warning around water problems are unmatched, and water conflict is a bipartisan concern, the U.S. should be reaching out to help, said Michel. “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

Specifically regarding Nigeria, King recommended the United States increase engagement and assistance by expanding research programs on drought-resistant seeds, assisting with “eco-regional conflict mapping” to plot ground water availability and desertification, and pushing for military cooperation to enhance environmental monitoring. “It’s an important time to husband our resources around foreign relations,” he said, calling for collaboration with non-government organizations and leveraging contributions from donor countries.

“In all regions, weak governance exacerbates these water challenges, and in turn conflicts over water resources make governance itself more difficult,” said King.

Event Resources

Sources: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Photo Credit: Displaced peoples near Lake Chad, January 2017. Photo: Espen Røst/Bistandsaktuelt/Flickr.com.